- Home

- Norah Lange

People in the Room Page 10

People in the Room Read online

Page 10

I don’t want to forget this night, because it’s late, and tomorrow I must ask them something. I think I locked myself in. If I could only wait until tomorrow to remember, but it’s her fault, just as it always is when she’s acting strangely, because she kept asking me, “Would you like a little more?” and I could hardly hear her, and I drained my glass of its yellowish wine and rested it on the table, and then I felt a slight lump in my throat, and the sensation began, and I felt like smoking, and the mystery, at first intermittent, then became constant, and a single phrase was enough, the three of them watching each other all the while, and I, from outside, from behind my throat, knowing they were taking the chance to speak, as I asked them questions, or fell silent as they spoke, and my hands, my hands felt like kid gloves, tingling with rows of tiny, cool ants marching up and down them, and suddenly, great clouds of flour upon my chest, leaving me unable to ask them anything. But it was beautiful all the same, because first she said—or perhaps they were already speaking, and I smiled to myself and the ants, sure something would happen to them, and to me, if they climbed any further up my arm. But I heard her say, “The best way is to slit your wrists underwater,” and I didn’t catch the answer, since the ants seized the moment to become more ants that tried to climb up my arm, over many sheets of newspaper. I would have preferred spiders to ants. The spider she found on her dresser, but I am not thirty years old.

When she said, “slit your wrists underwater,” I looked at the others, and they seemed ashamed, and their mouths became muddled beside a blue dress and an overly polite man who kept doffing his hat, and failed to find the suicide line on the palm of her hand.

But I must try to think of everything before I go to sleep. They spoke of “prepared deaths,” but it must have been the cool wine, because the other two didn’t say “suicide,” but “when one prepares one’s own death.” I imagined they must be ill, but no, it was another kind of preparation, one without any cure, and I remember other things, and thought it would be terrible if someone were to ask me, “How did she die?” and to be forced to explain, or wait until we were alone, because if I were to say, “She died a prepared death,” that person would respond, since no one understands the lack of a will to go on, “Was it a terminal illness?” and I would have to say, beside the flowerless coffin, “Madam. She died of a prepared death. It can happen so easily. One need only be sad.”

“She didn’t seem sad … ”

“Stop meddling in things you know nothing about. Only the ignorant would assume that someone shouldn’t die of sadness.” And then I’d go on in a gentler tone, “People get sad so that they can die happily.” And, if she truly annoyed me, “Don’t be so foolish. You should occupy yourself with other things. You know nothing of spiders. Look at yourself in the mirror, with that spot on your face. You ought to be ashamed. You ought to die of that spot, and not go around finding fault with well-mannered deaths. You shouldn’t even leave your room, and to think here you are, in the presence of death, in your hat and gloves, and your handbag stuffed full of essentials, and all that’s missing is for you to say, but you can’t, since there aren’t—thank God—there aren’t any flowers, that it would be a good idea to open a window.” And then I would shrug, and I’d be so angry, and I’m so angry now it seems it’ll all happen just like that, and that person will actually appear, and I’ll have to cry at her to leave.

I know she was the one to say, “People get sad so that they can die happily,” but I couldn’t admit to her that I repeated her every word. That’s why it was dangerous for me to be asked anything. The only thing I know for sure is how beautiful it would be to postpone it all—the desperation, the dizziness, my hands with the tingling ants now gone, the “slit wrists underwater”—and to be able to say, “in two weeks, in a year,” to keep thinking about it, but tonight I can think of nothing; someone’s knocking at my door, but no one seems to be there, telling me to go to sleep, because everything is covered in flour, in this urge to smoke; flour on my chest, under my nails, my hands so pleasantly submerged in flour, constant, replenished, as someone calls to me from behind the door, and there’s something I must remember to ask them, and perhaps this is how it begins, “What lovely eyes she had, everyone dreamed about you,” and no one must know that I’m surrounded by clouds of flour before falling asleep, unlike ever before.

18

I awoke feeling expectant and noticed the piece of paper on my table. I wasn’t afraid of the paper, after reading what I had written. It seemed a little sad and absurd for my mind to be crowded with so many thoughts, and for no one to notice. But there was the knocking at the door, and I couldn’t recall the stern voice, which might speak again any minute. I was afraid of having to explain something difficult, although, stated plainly, it was simple, so sadly simple, “I went to visit the people in the house across the way.”

Or, “I was at the house across the way.”

“People?” they would object, “What people?” and this last question allayed my fears, because it meant the others didn’t know them. I reread what I’d written, parsed as well as I could the two hours I’d spent in their house the evening before, unable to glean anything that could have caused such hatred or such affection. I turned the key in the lock, so the others could come in without knocking. I felt relieved, convinced something was going to happen; that I’d have to explain myself, that I might expose the three faces to danger. Perhaps it was better that way. If nothing happened now, it would soon be lunchtime, when someone—my God, who was it who knocked?—might ask, “What was wrong with you last night? Why wouldn’t you open the door?”

I still had time to think of an answer, but the tone, the shape of the resentment that might well up at any moment, those I couldn’t know. And they’d probably only knocked to ask for some lotion, or a book. Perhaps someone wanted to talk to me, the way we used to talk before the house across the way began. I couldn’t remember what I ought to ask them, and perhaps I’d only written those pages to put on airs. But if I couldn’t remember what had stirred me to write them, or the knocks at my door, then perhaps I hadn’t imagined the question, or the flour and the gloves. Because the flour and the gloves couldn’t be a sign of my putting on airs. And then I had no time left to think about it, because suddenly everything crowded in on me: the house, the courtyard, the geraniums, the dining room, my family in my room, questioning me.

“What was wrong with you last night?”

And now there they were, each wearing a different expression, with nothing to do but stare at me. I saw them approach my table, indifferent, not looking for anything in particular, but I had hidden the pages I’d written. I sat on my bed. The light shone weakly through the half-closed shutters. Everything happened as I’d expected. While the others tried to act unconcerned, someone asked me, “What was the matter with you? Why did you lock yourself in?”

I kept quiet. As long as they didn’t ask me if I’d been out, I could invent plenty of reasons for having locked myself in, but I needed to be quick; I couldn’t allow them enough time to think up their own, or give them a chance to scold me. I thought of telling them that I had been crying, but I stopped myself, because suddenly it all seemed unnecessary.

“I don’t know,” I replied. “I was feeling strange. I barely heard the door.”

“You were feeling strange? We’ve noticed,” but I didn’t let her go on. That wasn’t the tone I wanted their questioning to take. I couldn’t seem strange to them—it was dangerous, almost a confession of the three faces, the wine, so cool and recent.

“I felt ill, as if I had a fever. I heard the knock at the door, but I couldn’t answer.”

“But why did you lock yourself in? What if something had happened to you?”

Then someone else interrupted and I was scared, and began to suspect how this would end.

“She wasn’t feeling ill,” they said. “She was telling the truth the first time. She was feeling strange, just as we

thought. And it would be interesting to know why.”

I’d never been so frightened. It was as if they’d suddenly decided to undress me. Then I saw them pursuing me into the drawing room, spying on me, discovering the three faces at dusk, learning their names, their possible professions, the dates of their memories, the last of their dead; if indeed they were patient, if indeed they were patient enough to wait until I left and walked around the block, before returning to the house across the way; if they were patient, they should venture with me into countless nights without brightly lit passages, or staircases; only a drawing room with three faces learned from the street; if they were patient, they should hate them and love them and feel strange; if they were patient, if they were patient, my God, they should stare at me, and detect the three faces inside my own, intact, perfect, easy to bear, so terribly easy to bear.

But they weren’t patient, and another voice, the one I expected, murmured, “Leave her alone. It’ll pass. Anyway, it’s hardly a crime to lock yourself in.”

I thought they would never be done with my room, with the newspaper on my chest, but I was prepared for anything so long as they didn’t reach through my face, or through my habits, and find the faces across the way, and just as I thought their faces would pass unnoticed, the voice that never did anyone any harm suddenly added, as if forgetting I was still there with the three defenseless faces watching me from the night before, from many nights, “She hardly goes out anymore. She spends hours watching the street. She must be under a bad influence.”

Then I felt as if someone was beating me without warning, shattering a piece of something that was mine, strictly and patiently mine. Also, I thought, honestly mine. I understood I was now in the midst of danger, and it would be better to pass through it all at once. I thought of that saying, “Love soon turns to hate,” and that perhaps I could hate her, cry that she didn’t understand, that she was incapable of feeling her own face, incapable of committing a crime, incapable of looking the part. I saw the faces across the way, beside clumps of torn-out hair, long red scratches across impassive cheeks while my fingernails ached, while my fingernails waited for me to cry, “Bad influence? What bad influence?” and the three faces nodded, becoming passive and precise. What did they mean by a bad influence? How could three faces that scarcely stirred be a bad influence on me? Was it possible for a face to set a bad example? The example of stillness, of respecting a storm, of grieving for oneself alone? But they never asked for anything. But they liked to gaze at portraits hung at the height of their chairs … Ah, but the wine! They meant the slow and deliberate wine, or their conversations about death. But they had no idea what their conversations were about.

There was a long silence, my question hung in the air and filled with splinters, with stitches, with every awkward and insignificant pain, becoming larger and more unnecessary by the minute. I thought if they answered, “The three women across the way,” I’d kiss my parents and leave the house, without saying where I was going, until they returned the three faces to me unchanged, with nothing added or stripped away, asking for my forgiveness. But there was no need for that. It was even worse.

“How would I know? Books. She always has a book in her hand. Something she’s seen outside. There must be some reason she no longer reads in her bedroom. She’s changed. She hardly speaks to us anymore … ”

And that moment, that very instant, was the beginning of the end, as clear as a ship’s siren (though it might still be a few minutes away); though neither I nor anyone foresaw it; though it still seemed easy, possible to delay, if only I could cure myself of seeing them. It was as if something still distant was beginning to stretch its limbs, to clear its throat, pointing out episodes to a memory that didn’t yet want to remember, since it wasn’t prepared; changing me, changing my seventeen years, forcing me to forget my bedroom, the courtyard, my still-unworn dress, tormenting me, urging me to turn a deaf ear to voices I loved, to my favorite, fleeting corners. But I could do nothing, I swear, other than watch their faces closely, follow their complicated, disjointed conversations, so I could position them in my room before going to sleep, and wish—sometimes I had to admit—that someone else might be able to share them, arrange them, and not be afraid of them.

I stayed quiet, a little resentful, awaiting the sentence that would send me away.

“I think a change would do you good; you could spend a few days in Adrogué. Let’s think about it. They’re always asking me when you’ll go. You used to like going, before … ”

Before, I liked going to Adrogué. Before, I liked black velvet, playing card games, riding in carriages. Before, I liked my favorite tree. Before, I didn’t live among those faces, or my altered days. I decided I would go to Adrogué, even if only so this possible “before” might also be of use to me with them. So that I could say, “Before I went to Adrogué, you told me about prepared deaths. What have you been doing, while I wasn’t watching you?”

But I also thought, and it seemed pleasant, almost an adventure, that I would come back four days later, scan their faces and find them identical, a little less watched, but identical to my nostalgia; perhaps more mysterious and determined. What would their faces be like after four nights without anyone’s gaze?

But I was still in the “before,” and I was sure. Sure their faces belonged to me, that they endured because I watched them; sure no one else had ever shown them such patience, that no one else was capable of sharing them so much, of being so addicted to them; even of glimpsing them, seeing them shift inside my face, which must express—it was impossible that it shouldn’t express—their three faces behind my own, expressionless.

19

Sometimes I passed the time imagining the nights she cried alone at the edge of alcohol, with those effortless but dreadfully sad, unreconciled tears; those listless, ritual tears, which welled up almost baffled by themselves, by their own unfathomable, remote misery, which could only be explained with great difficulty; and I thought if someone were to ask me, “What is she like?” and I had to answer then and there, I wouldn’t be able to describe her, or remember her at the moment she did anything. If someone were waiting for my response, I’d only be able to describe the way she returned to her tears.

After a while—a few hours were enough—I would manage to conjure her in other gestures and careless habits. She seemed destined to be a memory, nothing more than a memory. The appeal, the happiness she might exude, began when her voice, the slow movement of her hands, were no longer too much of a hindrance or a distraction.

One night, she told me of how she would cry. The evening she cried in my presence, her brief and deliberate tears were easy to explain, since I assumed she was hoping that something, now lost, would come into the drawing room and settle down beside her, or beside one of the others. It might be a face, one face less, the same spider taking its usual path, the slit wrist of which they had spoken. I could also explain her way of crying alone because whole sentences she’d uttered followed me home, stretching after me uselessly; I couldn’t interpret them, or ask anyone to explain the many hidden corners of her fatigue and her selfishness.

“Some nights,” she said, “when my sisters have fallen asleep, I come back to the drawing room. I like to be in the drawing room. I can never remember anything when I’m lying in bed. So I sit in the armchair and smoke. I know I can sit there whenever I like, but I don’t want them to become accustomed, or to accustom myself, to the armchair seeming to be mine. I’ve never abandoned any habits willingly. And it’s too late to start now … If I’d thought of it before, perhaps I would always sit there so later they could say, ‘That was her chair.’ But it’s too late now, though ever since we’ve lived in this house I’ve noticed they seem to save it for me.”

I watched as she began her hurried tour through the scant list of memories she might have bequeathed them, had she thought of it before; hastily, distractedly, in the ruins of evenings that might still be left, in nigh

t-time fragments while her sisters slept: gathering white kid gloves, unmarked books, predictably slammed doors, the brand of her cigarettes, the day she braided her hair.

To help her, perhaps in the hope that she would leave more memories behind, I tried to counter her, “Memories are harmless. It’s lovely for you all to have your own routines. I like knowing that chair is yours, though I wish you would say so yourself. And if you did, perhaps the others might feel moved to choose their own. It would be such a small price to pay. I too would like to be able to say later, ‘That was her chair …’”

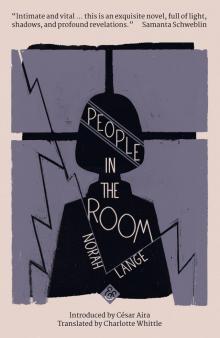

People in the Room

People in the Room