- Home

- Norah Lange

People in the Room Page 11

People in the Room Read online

Page 11

But she had already retreated towards her tears, and I could tell that she enjoyed them. That night, she asked me to come back after dinner, since it was her favorite time of day, and she would be alone for a while. I shouldn’t have accepted, since it meant seeing her another way, and I didn’t want to know her any more deeply, move any further into her private world, until the day came when I could listen to her with nothing to distract me.

That night she told me of how she cried. I remember how hard it was later, back in my house, to remember precisely how she broached what she wanted to say, and I even found myself writing down some of her words, because that must’ve been how she spoke to herself, to express her most intimate feelings, without anyone else knowing.

I knew she cried. I knew, too, that her tears were neither unexpected, nor startled by their own weight, but that she would wake up one morning, determined to cry that night. She needn’t be in a hurry, betray a different kind of sorrow, or even pity herself. It was enough to go through the day with her mind made up, knowing she wouldn’t fail, that nothing could make her delay it, as if, long before, she’d marked the date with a cross: “Tonight is my time to cry.” Calmly, as if awaiting something pleasant and familiar, she would sit with the others in the drawing room, go into the dining room, return to the drawing room after dinner, and then, when they said good night, she would undress and lie in bed, until the other two fell asleep. Then she would get up again, and, wrapping something around her shoulders, go silently into the drawing room, to pass the time with her tears.

Sitting in her armchair—so she told me, since I never saw her then—she would wait a little while, as if to settle comfortably. I don’t know what it was that she remembered, with which tearful word she endeavored to let herself go, since she never told me. Perhaps it was a “Farewell” tossed by the wind, which she couldn’t hear; someone murmuring, in a careless moment, “Blessed are the eyes that behold her”; perhaps a melancholy evening after a piano lesson. Since I knew so little, I couldn’t list all the likely scenarios: imagine a deceased father, her own predictable widowhood. I could only surround her with events reminiscent of the way she sat in the drawing room, and even then, it was so difficult that I had to write many things down, so as to try to understand them later, when I had the chance.

After a while, as she smoothed her nightgown over her knees—and perhaps that was the best, most solemn moment—a tear would come to her eye, though she would still wait a while before letting go. But not for long. Whatever was dwelling inside her would suddenly come to life, and—as if deliberately stirring belated farewells, blessed eyes, letters still unreturned, a piano in the afternoon with no desire to keep playing, two lifeless sisters, perhaps a wail beside the unworn gloves—with bitter sobs, motionless at first, then letting her tears fall onto her hands, onto her nightgown, she would cry for an hour, two hours, gazing ahead, not wiping her eyes, unblinking, as if posing for a weeping portrait, while her tears, like the first heavy drops of rainfall, bathed her nightgown, leaving small damp patches on her chest, on her skirt, that little by little turned cold.

When she’d finally cried so much that only rough fragments of sobs were left in her throat, she would get up slowly, return to her bedroom, not needing to turn on the light, climb into bed, and soon fall fast asleep. Sometimes she had to lie on her side so she couldn’t feel, against her skin, the final swollen drops of her deliberate tears.

20

I needed to rehearse, since the time was drawing near, and I had decided to spend four days in Adrogué. I mentioned my journey several times, without giving them a date. I was distressed to think of leaving, of abandoning their faces for those four nights. I understood a little too late that the danger had begun as soon as I had mentioned that I might go away, because the idea soon settled in beside them, and there wasn’t an evening I didn’t hear them speak of my departure.

“When you come back from Adrogué … ”

Even though I reassured them I could come back the next day, they corrected me, not even allowing me the solace of an unforeseen and pressing matter that might compel me to come home sooner than I’d planned. Patiently, as if needing to be sure—while I took pleasure in imagining that they spoke out of fear of missing me—they said again, so I wouldn’t keep making the same mistake, “But you told us you would be away four days … ”

Because I’d said I would from the beginning, it seemed I was obliged to stay away four days. But what I remembered most of all—and it always surprised me—was how earnestly they listened the first time I told them I might be going away. As if I’d just informed them of something very important. I noticed, too, that she turned to look at her sisters. Perhaps they were tired of me, but if that was the case, why did they invite me back, welcoming my frequent visits? I couldn’t feel—and it was essential to feel—their weariness: instead, I felt as if there was something I was delaying, or preventing, and since I couldn’t possibly prevent her death, I had no idea what it might be. Perhaps they would use my absence as a chance to forge their way out, emerge from their portraits, and close the window, finally, with a sudden, simple gesture? Perhaps, for a few hours, they wanted to cease to be the three faces across the way, without disappointing me? Perhaps they were waiting for someone, but would rather hide it, or they’d been afraid, since the evening of the telegram, that I might once again meddle in their affairs. They didn’t seem to begrudge me; it just seemed important to them, because she asked me, “When are you leaving?”

“Not for a while yet.”

“But when?” she insisted. Then I had no choice but to tell her.

“The fourteenth of September,” and her terseness, too, forced me to hide why I was going away, the reason compelling me to abandon them at the very moment they seemed least calm, when the house’s atmosphere was deepening with secrets. There were evenings when she seemed guiltier than ever, as if she couldn’t go on, as if she was on the verge of confessing to it all. Perhaps that was why (to tell the truth) they were glad I was going away, so they could reflect on her secret crime, on what must come to an end, certain that I would weary them with my persistent, impertinent questions. I couldn’t admit I was leaving because I’d locked myself in my room one night, and because my family thought I seemed changed, or that someone had described them as a bad influence, not knowing who they were; I couldn’t even allow myself to mention a birthday—a day which in that house might be heavy with omens—since surely they would think it absurd to celebrate a birthday, and I wanted to be like them, though I knew that to be like them I would need to get to know them more. It wasn’t enough to speak of portraits, dead horses; to raise my glass or push it away, as I did at home. The likeness should be remote, remembered later, casually; it should be different from me and from my way of feeling at ease. I couldn’t say for sure if I felt at ease sitting across from the three faces with which at first I’d passed the time, and had later come to love, even though they were merely the faces of three wayward women, three memory keepers who were occasionally wrong.

As I meditated on the date I’d so hastily made up, she said, “Eleven days from now,” and, as if effortlessly, through the cloud of smoke, she added, “We’ll miss you very much.” And then, even though I’d only mentioned it for the sake of saying something, or because it was eleven days away, or because one day I would have to change, and remember them from other places, I decided to leave on the fourteenth of September.

I felt vaguely comforted by the thought of telling their story somewhere far away, where no one would have any idea how important their presences were. I could try to explain that she was burning up inside. I knew the expression was common, and didn’t explain anything, but I could find no other that so captured what I wanted to convey. Sometimes it even seemed easy to touch my finger to the pain that must have been stirring near her chest, like a bruised and feverish wail. I was sure it came close to something that, suddenly, might break free like a flame, but

without the flame; something causing discomfort inside her arms, her hands, but especially in her chest, like a belabored sigh.

“She’s burning up inside,” I thought to myself, and it seemed fitting to imagine the swollen blue-violet wound behind her throat or inside a lung begin to catch fire, to spread like a tree until it choked her, branching around each bend in her arteries, while the two others watched her, awaiting the fire, the cry, the thunder (what do I know), except in troublesome, scattered fragments, all of a sudden. Only then would she reveal who she was and what she was hiding.

She announced that they would miss me in the same voice she reserved for momentous things. Her voice made me uneasy, as if she’d been postponing something for too long. I didn’t think I should leave without knowing what they were awaiting, what they were planning to do in the long years that lay ahead. Would they really spend their lives watching the street from inside their portraits? I needed to know more, so I could consider it during my absence, and try to solve the mystery. I needed to find out, at least, who the man was who’d visited them one Thursday. Suddenly I resigned myself. When I came back I would be bolder, would question them as calmly as they had spoken of slit wrists. Now—and I was getting impatient, couldn’t wait any longer, since I thought I’d overlooked the most important detail, and that it should have occurred to me sooner—I needed to know if the youngest had kept the packet of letters. I needed to forget her selfishness, the serious look she’d given the man as he leaned down, not seeing or hearing her, heeding only the skin he kissed, the gaze that perhaps had often made him cry. I needed to know if a furtive hand had opened her wardrobe, or a dresser drawer, to take out the envelope. I didn’t think I’d be able to bear it if she told me they’d burned the letters, that she’d been left alone, and hadn’t even been there to watch the small, secret fire of white paper, with an “I love you” that blackened no sooner than it was consumed by flames; that she’d always be parted from her palpable portion of past, which perhaps she could revisit when she had lost all hope.

I decided to find out that very afternoon, even if there was a chance the white envelope hadn’t contained any letters. As I spoke to them of my journey, and of how I’d still be able to see them several times before I left, I plotted the question. None of them noticed my impatience. Finally, the time came to say goodbye, and then, as she stepped forward to see me into the vestibule—they never came out to the front door—I managed to hang back beside the youngest sister, and, as I looked at her, I asked her in a low voice, “Did you keep the letters?”

My voice seemed to have reached the vestibule, to be echoing through the house, not finding an answer. But then, from some distant place, from the depths of my gratitude, of my joy at being alive, of my vigil, of my way of protecting them as I watched them—convinced of her selfishness—something touched me and I felt a lump in my throat, when I heard her whisper, as she looked at me with what little remained of her gaze from that evening, with a horse beneath the rain and the voice of a man in the gloom of a carriage, “Yes, I kept them.”

Then I went out into the street feeling grateful, grateful that I hadn’t been wrong, that the man deserved her, and for everything that might still live on in my presence.

21

I was often completely happy at their side, as if I were watching, without participating in, a beautiful performance that might go on forever, even if a scene were repeated or sometimes a conversation held me back.

That was how I felt whenever one of them declared, as if she had looked everywhere and was getting desperate, “It must be in the trunk.”

Then I would freeze, since I knew those words to be the beginning of a contradictory and happy inventory, refashioned countless times. I don’t know if they realized so many tangible, faded memories couldn’t possibly all fit into a single trunk, but as soon as one of them said, “It must be in the trunk,” the nearest voice would interject—as if it had come running from somewhere far away—and say something just in time to correct their mistakes, the shabbiness, the rust on their long sewing pins, the dusty white edges of a photograph album cover.

“No, no! How could you possibly forget? The lace is rolled up in a box, on top of Grandmother’s dress, with the fans. I stored it there myself. I still remember I put it on top of the other things, since you were planning to use it one day … ”

But the first voice kept rummaging through pieces of satin, peering out onto balconies with strictly kept hours; crossing a station left dusty and rattled by a passing express train; but almost always on a balcony, at dusk, when a trunk catalogued by the nostalgia of strange women was a prospect still far away. And as they smoothed out a piece of darkly colored felt, or returned a locket to its place, I thought of how there should be no such thing as fatherless women (children mattered little to me, I thought only of women), unprepared, suddenly abandoned when someone turned cold beside long needles slowly injecting an intravenous liquid; a bandage gripping a thigh, until the listless, futile dripping went on no more, and someone in the same room suggested potential funeral parlors, without understanding, without despairing to think of how unschooled they were after the way they smiled, the way they said they were willing to work, to be brave—when it wasn’t true, they, with their agonizing predicaments, weren’t even ready for the most ordinary happiness, or the recommended job, or the silent house with visiting days, or the moment they might be hungry—even if it wasn’t true hunger, but a hunger for small, varied servings—or to grow weary of things that were easy, of things that were too much, or of things awaited at the end of the day, the strict and calculated day that didn’t end with a belated good night in the certainty of brushing against the same cheek the next day. That was how I saw them, with no time to collect the last motionless sign, no time to collect the last stroke of courage, no time to collect anything that might convince them that life would be bearable after their father’s death, and something must soon be done; I saw them alongside somber women half in mourning who didn’t wear black, because “mourning is worn in the heart,” while they had dressed meticulously and constantly in mourning, since it wasn’t true that “mourning is worn in the heart” rather than the way they had worn it: in the bracelet they stored away, in their black suede shoes, until it invaded everything, leaving no room for a white ribbon, not for six months, or a year; it wasn’t true, it wasn’t true, because they wore their mourning at home, and in the street, they undid it against the walls when they came home at night, and they only had to swear they kept it in their hearts to start crying or slowly go mad, their fear swelling, taking up more and more space, fighting the love devoid of any final sign, as they became accustomed to fear or to love without long conversations, because their father’s death was something so dreadful, such a lifelong injustice, that they longed for deep wounds so they could rip off their scabs and cry, cry endlessly; hate everyone, and go to sleep at the same time, as if crying were the only respectable, bearable occupation, murmuring, “It isn’t possible … It isn’t possible,” as they remembered every detail, even the most awful, the most indecent, without recoiling in horror, without forgetting to wind up the alarm clock so as to arrive early. Because I saw them that way, and that way only, unwavering, drinking their cool wine in small dangerless doses, composing (a little weary or sorrowful) their memories of some man, and it seemed to me that they must hate even the dead, must wish for not a single one of them to rest in peace, since they had to survive without any sign, without the promise of a farewell. Then I remembered how they thought about death, and I was somewhat comforted as I saw the three faces biting their fingernails over their dead father, and I could begin to recognize them from many years before and reach them again, arrive on time for that very evening when one of them repeated her own particular consoling list.

“First, we decided to store Luciana’s clothes there, but there was still room left over. Then we put some of our own things there; my blue dress, the one with the ruffles,

I wore it twice … ”

“No, no! Your dress is in the trunk along with mine … ”

And they traced the white sheen of a dancing dress, a pair of cufflinks, a Bible, the portraits, some riding boots wrapped in brown paper, or one of them rummaged through a yellowing necktie, a felt bowler hat, an antique umbrella handle, while another voice added a silk shawl, two keys in an envelope, a dance card, their school uniforms. The trunk was filled to overflowing and couldn’t be closed, and the voices began to sound sad, since at least one of them knew there was no room left for her blue dress, or her cross-stitch alphabet. And when they began to despair because they couldn’t bear for their memories to fail them, the most desperate among them suggested a journey into nostalgia, a final journey before they put everything back in its place, until after a few days their memories faltered again, or, if one of them died, the other two, also mistaken, would perhaps manage to take a faultless inventory.

“Why don’t we open it up, so you can see? I’m so sure of it! … It seems only yesterday I folded that dress, so it wouldn’t get creased … ”

But when the moment arrived, she—it was usually her—would seem to suddenly lock the threadbare lace trim away, next to the detached fan ribs, and, as she quickly collected a final piece of muslin, a prize won for French, an unused bandage in a small box, and a dropper still coated with a residue of dried iodine, she would murmur, as if no one had died and my happiness meant nothing to them, “No. Not now.” Then the others agreed to put everything back in its place, each smoothing things out in her own way, until the next time, when perhaps they would be less doubtful.

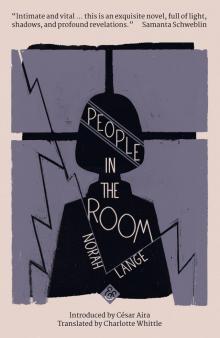

People in the Room

People in the Room