- Home

- Norah Lange

People in the Room Page 9

People in the Room Read online

Page 9

And as my mind wandered, wishing to find her alone, free at last from the destiny I forced her to share with her sisters, she looked at the eldest and declared, “Tomorrow we’ll go to the telephone company. We don’t have to answer it, anyway … ”

She stared at her evenly, without any sign of annoyance, and I had the impression that something just like a sudden sigh of relief had been set free, though not for long, since it would surely return to its place as soon as I left.

A week passed and I visited them twice, without daring to mention the telephone. One afternoon she said, while the two younger sisters stared at me as if it was all my fault, “Tomorrow they’re coming to install the telephone,” and murmured two numbers, which I collected carefully, taking my leave earlier than on other days, to allow them a final evening alone before the change, leaving each to her suspicions, to her way of preparing to turn a deaf ear to the telephone as soon as its shrillness startled the house, determined not to answer, even though they were convinced that no one knew their number.

The next day, after the telephone installers had left, I observed the faces from my window. There was nothing to suggest they were afraid, that the telephone was there in the vestibule, irrelevant and useless, imbued with voices that were strange or sweet, insolent or intrusive. I looked at them many times before deciding to hear their voices, to confirm their variations, their timorousness, as if someone was watching them, forcing them to speak to people they didn’t know, and perhaps hated.

I went to my telephone, picked up the receiver, and recited the numbers after two zeros, not preparing my words, since, in fact, I didn’t know what to tell them. It seemed rude to call without having asked them first. I shouldn’t have been so cruel. It wasn’t my place to be cruel. Nor could I ask, “Is that you?” since even if one of them confirmed that it was—without my knowing to which of them I was speaking—it would be absurd to tell them that I lived across the street, the only proof of my existence during the moments they couldn’t see me.

I listened to the telephone’s low hum, which stretched out monotonously, until the operator said, “There’s no answer,” and I replaced the receiver, as if I’d lost them again. I went back to the drawing room to watch them, thinking they ought to answer and get used to being brave. None of them had moved. I decided to cross the street and tell them I was going to call them, and that they should answer, even if only so they could get used to the telephone.

“All you have to do is lift the receiver and ask, ‘Who is it?’” I explained to the eldest, hoping she would be the one to answer. It was too much to tell her to say “Hello,” since I knew she would never dare to utter it. The “Who is it?” might, on the other hand, bear a likeness to many things that could wound them, but in a familiar way. When I begged her to answer, she accepted, sadly, as if I was demanding a sacrifice.

Before asking to be put through, I stood by the telephone for a while, so my voice would sound as it always did. Then, determined to face her, to tell her my name and all the clear, inessential things I’d never said in her house, I murmured the number to the operator. I thought I could beg her to let me speak to one of her sisters so she’d have to ask me which one, and then tell me her name. The hum lasted a moment, then suddenly stopped. Someone had lifted the receiver. There was a silence, which began to expand. A few seconds passed. My silence mingled with hers, wrapped around it, seemed almost to touch it, as if an unexpected hand had brushed against another in the dark, unable to say precisely to whom it belonged.

I would have preferred to feel the silence less; I would have preferred to be brave enough to ask, “Is that you?” or to ease her fear by murmuring, “It’s me,” but then the “It’s me” might sound like a different voice departing from a happy summer, and she might make a mistake, forget it was really me and not some presence emerging from a fated evening to tell her again that it loved her, or to say, simply, that life had forced them apart.

When the silence had almost swelled to a sob suspended in the air, gently, taking care not to hurt her, trying not to let her believe I was abandoning her, I replaced the receiver and returned, slowly, to my window, my silence unbroken, tender, while she too returned to her place.

The next day I waited for her to mention it, but she said nothing of our silence; we spoke of other things, and only when she showed me out, as if she’d reached a conclusion after much deliberation, did she say, “Sad people are almost always well-behaved.”

Even though I didn’t like the way she looked at me, I said hurriedly, “Your sisters are sad and perfect … like you.”

“They started too late,” she answered, and, after a look that soon seemed to grow weary, she said just what I’d hoped, and would always be grateful for, even though I was scared to death, even though it forced me to flee and not visit them for days on end, because I didn’t want to be like them.

“Perhaps if you were to start now … ”

I never called her again.

15

I know I was wrong to turn on the light, startling them with its unaccustomed glare, though no one else would have thought it such a terrible thing to do. From the moment I decided to do it, though, something told me I shouldn’t. But everything, in their presence, acquired gravity, a sense of parting, of bitter oblivion, of mysterious, ineffable ways. To make myself feel better, I thought of how some people can be wounded forever by the slightest look. Others, though, may have their hearts touched, their most hidden pains revealed, be reminded of a name they were once called, and simply smile, as if it would take much more to hurt them. But not them. Whenever I stood up suddenly, or one of them said, “It’s Monday,” it was as if something fled in fright from the scraping of my chair, or as if we had to meditate for a while on it being Monday, placing it among important days with promised candles, because it came from far away, laden with red, foreboding signs, so they could claim it as a premonition.

I also knew, when I visited them, that rather than having them within reach of my hand and my voice, what interested me most was to keep watch on them. To keep watch on them uninterrupted, even if they sat in the same place all night, smoking incessantly. There was always a chance of a subtle change; one of them would stop watching the smoke, another might say something about a mirror or a marble staircase, and I could collect those words as if they were the secret key to other episodes they hadn’t yet revealed to me.

I shouldn’t have done it, though, and later it was useless to tell myself so, useless to try to explain myself, in the hope someone might ask me why I had acted that way, only for me to remain silent, since no one else knew that house, or their faces lined up in a row. Of course, a stranger, someone with no attachment to them—not to the way I might describe them, nor to a certain kind of sadness, someone who, at the very least, had some respect for the vague outline of a wish, for a favorite flower, for a yearning for rain—might consider it all to be useless and far-fetched, my suspicions excessive. But I was consumed.

Sometimes, back at my house, I would toss a book onto my bed, have a drink of water, or laugh just as I used to, and I felt the three faces crossing the street to admonish me, or to tell me I was making gains. I knew if the faces crossed too often, I could always escape. I needed only to expose them, and perhaps smile, as if their faces had come to an end. But that was a long way ahead. The mere thought of smiling after telling someone about them saddened me, as if I’d been asked to describe the face of someone who’d died.

One evening, I decided it wasn’t enough; it didn’t suffice to spy on them, or to sit with them so I could watch them. Nor was it possible for me to visit them more often. And at that moment I had a thought of which I’d never believed myself capable, as if I hated them, as if I’d wanted to humiliate them, to throw them into disarray forever, force them to banish me, and for their hatred to pursue me for the rest of their lives, when in fact I loved them so much that at that precise moment I would have done anything they’d asked.

We were in the drawing room. It was almost time for me to go home. The lamp they always used scarcely lit the room’s corners, but its dim light fell on the three faces, and was magnified by them. One of them recalled a blue dress stored away in a trunk. She seemed to be enjoying the memory, as night drew on. I thought the blue dress must have suited her well, much better than those dark, charcoal grays they’d worn ever since I met them. I thought their dresses might be to blame for many things they said, or that they at least were a change of topic. Because even if they said words like “street,” or “station,” those words always gained a new meaning in their mouths. When other people spoke of such things, everything stayed calm; too calm. But when I heard her mention the blue dress, I sensed the difference at once. I believe the idea began in that moment, on some breezy boulevard she must have walked along, on some balcony she had looked out from—free from the weight of her mahogany wardrobe, burdened by such dark colors—her arms adorned with bracelets, as someone came around a corner. I wanted to see her more clearly, to see how she looked when she said, “blue dress,” beneath the overhead light.

Unnoticed by them, and in the silence they seemed to let fall and be filled with a sad, mothless dust, I looked around me, to see if I could find the switch. The chandelier hanging from the ceiling had four lights. I had never seen it lit. I thought I could say my goodbyes, and press the switch as if by mistake, distracted. The blue dress floated in the distance, beckoning me from above their faces, shouting at me, laughing, descending a marble staircase, hiding behind a column, leaning over to tend damp ferns, giving me the strength to look at them squarely. Then, almost automatically, since I’d already decided, I got up and walked towards the door. I remember murmuring, “See you tomorrow,” and my voice seemed to say it as if many things should be resolved by the time I saw them again, and when they answered, “See you tomorrow, God willing,” I stepped away, towards the door, pretended to have forgotten something, and, leaning on the wall with one hand, I pressed the switch.

The drawing room lit up with a glare that startled me, too. I managed to force myself to murmur, “I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to.” But it was too late to forget. I would never be able to forget it, because the room seemed to fill with blue dresses, with uncovered arms, bare necks, but most of all, with something cool, endlessly cool, and when I looked at them, one by one, it was as if, in a dark room, their three white faces—waxen, framed with lightly starched lace, and gathered in a beautiful vigil—had been cast by a spotlight onto a screen.

She flinched and lifted a hand to her throat, as if to clutch at a necklace, and then she cried:

“Turn the light off! You should be ashamed!”

“I’m sorry,” I murmured again, and, without touching the switch, I fled from the room, determined not to come back, since it would be impossible for their faces to have a more beautiful ending.

16

Occasionally I thought about how someone might suddenly ask me, “What are they like?” then wait for me to describe them, to note the color of their eyes, the shade of their hair, or to say, at least, if they were beautiful.

The possibility was enough for me to strive to recall the narrow space of a forehead, the different ways they smiled, but I could only ever manage to recollect straight hair, perhaps mistaking it for theirs, convinced it was straight since I couldn’t conceive of a dead woman with wavy hair; I was sure her icy temples, and her skin, now free of restless blood, would make her curls disappear. I imagined, too, that the beauty—the final mystery—would all be in her face, in the frosty, taut wax, which every gaze would fall upon without seeing. A death of the face, of the face alone, also hinted at my own, but I was convinced my wavy hair and its occasional shine disqualified me from an early death. I could swear their hair was straight if no one demanded any details, but even if no one was waiting for an answer, the “What are they like?” would expand, grow insistent, and despite the question’s simplicity, it would prompt me to roam among their features, unable to hold on to a single one, or else I would get distracted by remembering other scenes that shed no light on their faces: fragments of conversations; the afternoon they declared their preference for short sleeves; immediately—as I always did when they told me anything of the kind—I managed to spy their bare arms, or a black ribbon at her throat, like the time she considered the possibility that one of them might marry, and for a while she went into mourning.

At other times, the “What are they like?” forced me to rush, and then it seemed to me that their heads were glued to their bodies—like those of pale, almost blushing porcelain dolls—and the place where they were joined, where the porcelain head and shoulders lay against the sawdust-stuffed body, could only be seen by undressing them. But I liked them all the same, and it seemed fitting for them to look like dolls, since they never turned their heads to address anyone, and it was as if their necks really were stuck onto their chests, the head and neck forming a single piece, with the necessary small patch of skin above the dress, scarcely a different shade from the lace collar.

I often forgot their faces at the very moment I needed to describe them, then spent the whole evening asking her (of course, I could only wish to ask her), “Where were you last night? Where were you last night?” and she would answer, “It isn’t time yet. I saw a man cry … ” And this intrigued me, and saddened me so much, and I was so sure I need only cross the street and ask her, “Where were you last night?” for her to answer, “I saw a man cry … ” that even though there was a chance she might be angry, or her answer might be hampered by a sudden pain, I forgot the shape of their mouths all over again, because I would choose that moment, as she cried at me to leave, to look at her squarely and say, “That’s what you all get for not dying.”

When I endeavored again to describe the curve of their eyebrows, without imagining them—and it was essential to envision them in the moment I repeated, “That’s what you all get for not dying”—it was comforting to convince myself that in my case too, everything that happened—the drawing room, their three faces, the way I had changed—was a result of my not having died. Except that I didn’t meditate on my own death, and when I told them this I planned to remind them, vaguely, that unless they transformed their lives, they ought to die. But it was so hard for them to change! Then I considered that for a while, and forgot their mouths, their foreheads—there was barely any room for their straight hair—because if they disagreed with me then they would have to leave, since I would always be the way, the witness to their thoughts. Perhaps I was taking myself too seriously, but the fact was, I would always be the one to have heard her say the words “slit wrists.” When I thought of how it was my fault that they’d have to leave, I tried to remember, to gather other things unlike that part of what passed between us, and I scanned the drawing room, seeking refuge in ordinary things, until my eyes came to rest, relieved, now far from their eyebrows and cheeks, on the two portraits hanging side by side on the wall. The portraits were beautiful, and placed very low. When I asked why they were hung so low, they answered that they always sat facing them, and wanted to have them at eye level. They wanted to watch them, as if the two faces pictured there were simply lacking the back of an armchair. They said, too, that it saddened them to have to lift their gaze whenever they wished to see them, since that meant choosing to look at them deliberately. This way, though, they could glance at them from time to time, as if the portraits were leaning against the backs of invisible chairs, listening to their conversations. Their explanation, as endearing as it was, didn’t prevent me from feeling slightly unnerved as I passed by them; it was like looking at a face that reached the height of my waist. I thought one day perhaps I would tell them this, if they forced me to be unpleasant.

At other times, convinced I could copy one of their profiles without any mistakes, just as I decided to trace the perfect likeness of a mouth, the “What are they like?” would drift away again, because it was impos

sible for me not to cry, “They’re dead! They’re dead! I’m telling you! I saw them, I saw them dead! They’re so far dead, a horoscope of blood could bear witness to it!” And by then it was too late, too late again for a long time, because everything became a blur, and, little by little, the scant pieces of their foreheads became a mouth that emerged from the side of an elevated cheekbone, veiled by the smoke of so many cigarettes, and I could only reach their hands, trying, for the last time—though briefly—to grasp at some eyelashes, a chin unstained by tears; trying to remember, at least, now that I was losing them, the modest patch of porcelain chest above their lace collars, but not even the shape of their dresses, floating, salvaged, was left.

17

How strange to write by night, in gloves, with hands like swollen gloves that float, or grip the edge of the table, while nothing spins around me; because it isn’t true, I can’t be dizzy. Leaning too far, perhaps, but I like how the gloves grip the table, because I want to remember everything, while I’m still up, alone, now that I’ve left their faces, their unshakable, unchanging faces. I’d like to give them a shake, to make them blink one eye after the other, or make one of their cheeks fall off; I’d like to hurt them by tearing out clumps of their long hair, leaving it disheveled, despite its shine, since they might lose it anyway, in a terrible north wind when the house is open, as I cry at them that they aren’t people, and death isn’t theirs alone, and anyone could sit patiently, their hands in their lap, without portraits. And then I know, I know I’ll say it; I’ll close up the house, and take pity on them. Or I’d like to spy on them as they get ready for bed, because they’ll take off their frills, and a slip with a narrow lace hem, or perhaps a brassiere; perhaps the happy moment of unhooking their brassiere because they finally seem to be alone, truly alone and at ease with themselves, perhaps without anything fallen or sad, just useless, simply useless, this habit of undoing laces and buttons, once the time for company is over. Perhaps it won’t be sad for them, and nothing will be any different, but still I’d like to spy on them as they take off their stockings and hang them over a chair, and then pull back the covers, and stretch out between the sheets, since they mustn’t curl up, but lie like the dead, or as they pray, and read, or kiss a portrait, but they don’t seem like the kind to kiss portraits. I’d like to spy on them as they go into the bathroom, and cry that I can see them in there, visible in their pallor, one after the other, each waiting her turn, running the faucet so no one can hear. But I could never cry at them to turn off the water; I couldn’t hate them that much, as they brush their teeth, and I smile at the foam left on their lips, even if then they put on some makeup and take some pills or rinse a pair of stockings and wash a handkerchief, and then stretch it over the tiles to dry flat. No, I couldn’t hate them that much, but still I’d like to shake them roughly, turn on all the lights in that respectable room, cry at them that they know nothing of dead horses, that they lied, or take my own life and beat them to it, if she really is planning to take her own life, and let them read my palm as I lie dying, so she will always misread her own, and then she won’t know when she’s dead.

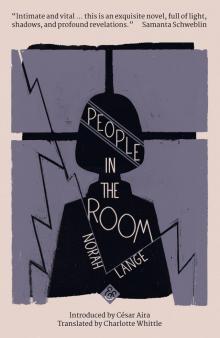

People in the Room

People in the Room