- Home

- Norah Lange

People in the Room Page 5

People in the Room Read online

Page 5

I didn’t dare look at anyone, in case I smiled, betraying that I’d only been putting on airs. My eyes fell on my empty glass, and it seemed to me, more than ever, that any situation could be redeemed by wine. So even though I almost never drank, I lifted my glass and said, “I’d like some wine this evening … ” Somebody filled it, and I mumbled a “Thank you,” as if the “Thank you” had been rescued from pain or bad news. I took a few sips and closed my eyes, forgetting I always closed them to savor the first few sips, and that this time, I ought to do something different. No one took any notice of me. As they spoke of a bride, I imagined a stranger sliding a card under my door; the card bore the words, “Your mother,” which meant I wasn’t my mother’s daughter, and that the mysterious woman, whose name I didn’t know, was wishing me dead in front of my portrait, which she turned to face the wall.

I ate a few mouthfuls and sipped my wine while the story of the bride ended badly, and in the silences between their words, I imagined myself so pretty and sad that my mother tucked me into bed beside an open window, so the neighbors could see me as they walked by. But the three faces didn’t turn to look at me; they were too proud, and then, tired of my coyness passing unnoticed, I took advantage of a pause in the conversation. Although the wine was appealing, I didn’t really enjoy it, and would have preferred to feel its effect without having to drink it at all, so I set my glass on the table, and finally asked, “What does it mean when somebody says, ‘We are always at home’?” But I soon saw the danger, and I blushed. I blushed so much I felt as if my forehead would set my hair on fire. I looked around at the others, wishing the blood, the wretched blood that was ruining everything, would drain from my face. I looked from one beloved face to another as the rush of blood subsided, leaving me weak; briefly, I collected everything I could from them at that moment, and then looked down.

“Is that why you’re behaving so mysteriously? Who told you they’d always be at home?” And then another voice added, “Were they inviting us as well? Who are you talking about?”

I felt as if they were backing me into a corner, demanding the three faces. I knew they were acting out of kindness, but also that this kindness might destroy them. It was enough for them to sense how close the faces were for everyone to run out into the street.

“Show us the three faces!” they would cry, and spy the three plain, defenseless faces through the shadows; shattering, erasing the night of the storm, the telegram, their acceptable, unshared presences, with a single gesture. And then perhaps the shutters would close forever on the house across the way, and their hatred, or worse, their disdain, would cross the street every day, at any hour, because they would recall the telegram, and be convinced I couldn’t keep a secret. From my place at the table I was already in the corner, shielding a brow with pale blue veins, drawing a veil over sorrowful necks, folding my napkin, trying to keep from having to fold up their faces and stow them away, swallowing the last sip of wine, bitter to me now; and I didn’t deserve to be putting on airs, I was incapable of deserving their faces.

“Who are you talking about?” someone asked again, scorning them, opening doors, threatening changes.

“They weren’t talking to me. I overheard one woman say it to another … ”

“Let her be,” murmured the voice forgiving of flashes of lightning, unmarked books.

I had already folded my napkin, and stood up, but I didn’t want to leave, since they still hadn’t explained the meaning of the phrase, and even if I already knew, I wanted to hear it, to be sure.

“What does it mean?” I asked again, hoping for some comfort, for the three ill-used faces to be returned to me intact. I wanted a peaceful evening, an evening full of hope. Thursday evening with its impending visit was already quite enough.

Then several of them began to talk at once, but I chose—I had just long enough—what I wanted to hear, the simplest part, to take with me to my room and savor ahead of time.

“It means that person will always welcome the other into their home, and, to be more precise, that they’d like them to visit.” I looked gratefully from my corner free of grasping hands, slamming doors, pieces of faces fresh for a fierce game of patience by the window, and stood up, taking the carefully stored words with me, so I could take them out later, when I’d said goodbye to their faces, when I was lying alone in my room.

“They’d like them to visit … ” And as I fell asleep, I imagined that very night she would be murmuring similar words.

8

At lunchtime no one mentioned the night before, but for me that day went by as if the house across the way had come to an end. I watered the begonias, tidied my books, polished the silver, and only once did I look out into the street. In the afternoon, I did the same.

They were in the drawing room, as always. I watched them at length, as if I had all the time in the world, and when I remembered I’d finally met them, for a moment I was surprised to find myself neither glad nor afraid, as if some remote but logical force bid me pause before I could feel joyful or sad about how much I’d gained. No matter how amazed I was to have come so far in just one day, Thursday evening still lay ahead, inevitable and uncharted. Perhaps they too wanted to get through Thursday before I visited them. That night I went to bed early, abandoning their faces for the first time.

When I awoke on Thursday and remembered the visit, I began to move slowly, trying not to put a foot wrong, since any sudden gesture, any ill-timed word, could be a bad omen. I was almost afraid to leave my room; someone might fall ill, and perhaps I’d be the one chosen to call the doctor, to change the cold compresses on a fevered brow. At lunchtime, I spoke of trivial things so the talk wouldn’t drift towards dangerous territory. The early afternoon went by more quickly, and I was relieved when everyone went out. The street was deserted; our drawing room was, too, and I shuddered at every sound, as if all things hinged on that visit. It vexed me to think that first the afternoon must pass, and I even disliked trying to guess who it would be; the hatred, the inconsiderate message that gave no time of arrival were enough. It began to rain. I was afraid he wouldn’t come. Perhaps the rain bothered him, too.

The streetlamps were already lit—it must have been around half past six—when I heard the clatter of horseshoes on the cobblestones. The light was on in the window across the way; the three faces, behind the curtains. Though it annoyed me, I had to admit it would be lovely to see him arrive beneath the listless rain, in a carriage. I was trying to guess which direction the horse was coming from, when I noticed the carriage had stopped outside the house across the way. The faces didn’t move. I went out into the street to get a better view. The carriage hood was up, and the driver had rolled down the black oilcloth used on rainy days. As I was stepping to one side I spotted a man emerge quickly from the carriage and ring the bell. I looked at the three faces, which in turn looked at each other, but none of them got up. The light came on in the vestibule. The maid answered the door, and the man stepped inside and took his hat off. I stood on the path, and even though I knew I would hate him, I hated him even more when I saw him lean gently towards them—a strange and unaccustomed presence in that room of three unvisited faces—then sit, probably at her request, in an armchair with its back to the street.

His presence didn’t interfere with my view of their faces, and I waited, almost wanting them to smile, for their expressions to change, for one of them to hold out her hand and accept a piece of paper or a check; that way, I would be disappointed, and could abandon them once and for all. Only the driver, the horse, and I were left in the street. The driver had been asked to wait; that meant it would be a short visit. But how could he visit them when surely the carriage had to get back to the station, and the streets of lower Belgrano were flooding with rain? And if he couldn’t stay long, as I myself wished to stay, and listen to them forever, then why was he visiting them at all? Perhaps he was in love with one of them, but was afraid to show it? Perhaps all three were

in love with him, and would have to decide that evening which of them was strongest? Perhaps her death hinged on his words? How could he speak so calmly when the carriage was waiting? My hatred kept shifting, occupying unexpected places, and so as not to hate him more, I watched the horse with its thick, shiny coat, which from time to time suddenly flinched, causing droplets of water to roll gently off its back. The driver had taken shelter inside the carriage. No one could see me, but I too was getting wet, in front of their faces. They seemed to be speaking in low voices. There was no change in their roles. I saw a small burst of flame each time one of them lit a cigarette. The man seemed to be speaking, and they only listened. Eager to see them more clearly—as if wanting to rehearse my own visit—I decided to move closer. I went in search of an overcoat, stepped out into the rain, and walked behind the carriage, towards their window. The raindrops falling from the trees seemed to lessen my hatred, but didn’t dispel it completely. The eldest was sitting at a slight distance, the other two to one side; but the three faces were still in a row, which allowed me to collect them, sharply defined. From where they sat, they could look out onto the street with ease. The man had his back to me, and I could only see the dark patch of his head, and a white strip of neck. Occasionally his hand brought a little movement to the still, startled atmosphere of the room.

Then I looked at her again. There was a white packet beside her that looked like a large envelope. Every so often she rested her hand on that patch of white, as if needing to remind herself of it. The third spoke, and she turned around, and stopped her gravely. I thought she seemed selfish. I thought whether the man came back, or left for good, would depend on her death. I thought it was a pity the man didn’t smoke, and assumed he would never win her. There was a small table beside her, with a decanter and a small glass. I could tell they were drinking since only one glass had been left on the table. I remembered the wine I had drunk the night before, and I thought she could easily win by drinking wine and smoking, since the man only took a sip out of politeness. I thought the man could win her by having a drink. But in that case, he shouldn’t have asked the driver to wait for him. I remembered that all this was happening on Avenida Juramento, across from my house, as it rained so close to their faces, and on mine, on the carriage, on the patient horse, and it seemed as long as I was still young, nothing so complete or perfect could ever happen again. For the first time, I regretted not sharing their faces, not sharing that scene where their faces mingled with a stranger I no longer hated so much. I almost wanted him to win.

I didn’t have long to speculate; I was distracted by the beauty of it all, and my mind began to wander—until she stood up. All her selfishness rose with her when she picked up the white packet. The man also rose from his chair. The other two remained seated, as if striving to prolong the beauty, to prevent her from handing over the packet, to stop the horse’s hooves from echoing that it was all over: my hatred, my keeping watch, my wishing to see her dead, as long as they didn’t gather their faces together, or shout, or go out into the street to watch the rain. I thought her words must be full of illusions, repeated postponements no one could believe—“They could at least wait until I’m gone—” and the man and she both knew that she was lying, that she would never die, and they were tired of waiting, while outside it kept raining beside a pensive horse.

Then the man stood up, determined, and she handed him the packet I was sure was full of letters. I thought—I had time to think—it would be stupid of him to take the packet, to listen to her, that behind the three faces and the unsigned telegram nothing would remain. Perhaps she had insisted he never write his name on any message, but the letters bore his signature. I thought it would be stupid of him to take them, because he’d leave them behind in the carriage, and the driver wouldn’t know what to do with so much vengeful love, with so much love that I couldn’t wait any longer, but only wish him a terrible, sudden end. But then the man did something I’ll never forget, something so perfect, so clear and final, so much to my liking, that I thought he must have won her forever.

When she held out the small packet, he took it from her, and, turning to the youngest—I assumed she was the youngest—who’d been watching him since he’d arrived, he placed it very tenderly in her lap. She was taken aback and raised her hand in fright. Then the man leaned over, took her frightened hand, and lifted it slightly, just high enough to kiss it slowly as she watched him, winning all the while. They were both winning. I couldn’t tell whether she was pretty, but instead I saw how she gazed at him; she gazed at him with all her being, with a long, deliberate, pensive gaze that began somewhere so distant and deep inside her I thought it would go on forever. The gaze lasted a few seconds longer, and she was winning all the while. Then, instead of letting drop the hand he’d kissed, the man seemed to return it to her, laying it in her lap with great care next to the white envelope. Once he had returned the hand he’d kissed, he stood up straight again, bowed his head slightly, and disappeared from the room. The one standing didn’t show him out. She stood, motionless and stiff before the others, facing the one still softened and surprised, with the white bundle in her lap, as if exhausted from looking, as if all her strength had been spent in her gaze.

Then I felt desperate, and decided to intervene. I turned quickly towards the front door. I waited for the man to come out, and when he was already inside the dark carriage and the driver was climbing up into his seat, I couldn’t help it; I moved closer, and peered under the hood, so the lamp shone on my face.

“Are they all right, sir? Can I see them?” I asked him beside the lamp, beside the pleasant smell of wet oilcloth, beside the horse beginning to chafe at the bit, and beside everything I wanted just then—forgetting my recent hatred, full of pity, convinced I must do something soon, before her gaze came to an end, before the horse set off and the man wept in the gloom of the carriage, not caring about the train, perhaps not even catching a train, only accepting that gaze, filling himself with the gaze I had seen.

And beneath the rain his voice, which also seemed wet, falling listlessly, monotonous but beautiful, asked me:

“Who are you?”

“I … live across the street. I knew they were expecting you.”

“Tomorrow would be better, miss. It was a painful visit.” And, gradually, his face, sheltered by the carriage hood, his voice, smelling of raincoat, and my favorite tree, suddenly visible as the carriage drew away, revealed themselves one by one.

Everything was perfect. His voice rising as if from many seats, the driver on his perch, passing just then beneath the streetlamp on the corner, conjuring echoes, perhaps causing someone to lift their gaze, and the people who lived in those houses to think, “A carriage is passing … ” though to them it didn’t matter. For me, a carriage was passing, without a bundle of letters, and with my hatred, which had come to an end.

9

I could hardly believe it. It didn’t seem possible that the moment had come for me to cross the street, ring the doorbell, wait for them to glance at one another before passing through the vestibule towards my unexplained presence, while I forgot the first thing I was going to say, and she opened the door slowly, perhaps not expecting me, perhaps wanting it not to be me. Was it possible that they would let me into the room I had learned by heart from the street, that they would allow me to sit there, facing them, so I could begin to weave stories about them? There would be no going back once I visited them, but I couldn’t keep watching them either, since it was no longer enough for me to gaze at the line of pale faces from my own house. Everything had changed, it was my fault, and anything could come between them and my way of watching them, and destroy what had begun, what had scarcely begun.

But it was no longer possible to just watch them—and even if I were pained by my urgent desire to see them, visit them, and make plans for things beyond their faces, I still needed to know how strange they were, whether they were really worth watching, whether there w

as more to them than my detailed vision of three women passing the time with similar destinies; three women in white blouses, who drank modestly at dusk, and who, when I asked them, “Do you remember?” tried not to let slip any shred of their past, but instead withheld names, allowed me only to glimpse a certain date, a high wall in Palermo, and if I kept asking—since now I knew the key to their presence in the drawing room—drifted away into bleak, undiscoverable terrain.

“Tomorrow would be better,” the mournful voice had advised from beneath the carriage hood, and now here I was on that tomorrow, having carefully replayed the scene of the envelope, of her selfishness, so that I could set apart the gaze of the one I’d always thought the least important of the three. But it was impossible to see it that way now, to allow her recently kissed hand, the hand he’d kissed ardently, eternally, to be placed back in her lap, to remain unimportant for long, though no one knew why. Perhaps the eldest considered it the gesture of a man who was often wrong. Perhaps she thought herself more important, because she was going to die. Then I pitied myself for knowing so little. I’d only seen her hand over a bundle of letters the man accepted, then returned to the youngest, collecting her gaze before he left. It was all he had taken with him. Perhaps she’d acted that way for her own good, but I was sure no one ever gave such a look for their own good.

That was why I wanted to visit them that very afternoon, before they could change, while a trace of her gaze still remained, and remembering Thursday still gave me strength. I had to wait for darkness to fall and for the streetlamps to be lit, to see them sitting in their drawing room, for everything to begin as I wished—including that first sentence that might force them to speak, force them to be sad or displeased, or to ask me to leave and never come back.

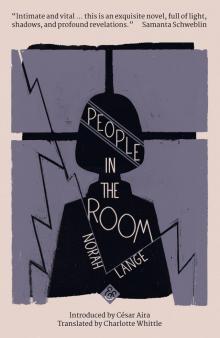

People in the Room

People in the Room