- Home

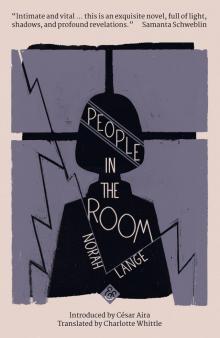

- Norah Lange

People in the Room Page 2

People in the Room Read online

Page 2

It is significant that the protagonist should be an adolescent, on the threshold between girlhood and womanhood. Adolescent girls are Lange’s protagonists of choice in everything she wrote. What seems to have appealed to her is the moment when childhood games encounter adult decisions. Or, to be more precise, the moment when the game of inventing imaginary friends becomes the literary game of the novelist.

Critics agree that People in the Room is Lange’s masterpiece. That scene of the adolescent girl and the three women, which remains frozen in mystery, and where no narrative unfolds, provided the perfect opportunity for Norah Lange to deploy her prose woven from silence, poetry, and ambiguity.

Lange was a novelist of interior spaces. She trained her gaze on hidden family conflicts, and away from the possible distractions of nature. Her last novel, El cuarto de vidrio (The Glass Room), turned the screw even tighter on the question of confinement, with a room made of glass: a terrace furnished as a dining room, surrounded by glass windows.

Comparisons of Lange with writers of the French nouveau roman, which paint Lange as a precursor, are not entirely convincing. Perhaps the sense of familiarity has to do with the period. Here and there, certain similarities can be detected between Lange and Nathalie Sarraute (where language takes on a life of its own), Marguerite Duras (in the way female characters shift and hide, and a resemblance in certain feminine atmospheres), and even Alain Robbe-Grillet, in the play with spaces, the architectural games of a novelist. Except that, unlike in the work of these objectivists, Lange’s houses become animated with a life all of their own. In one episode from The Glass Room, a female character is forced to spend three months with half her body enclosed in a cast to correct a spinal curvature: a “femme maison,” just like in the painting by Louise Bourgeois.

I said earlier that all of Lange’s early work, up until Notes from Childhood, could be explained autobiographically. Then came her most authentically original work, her novels—those strange meteorites unlike anything else that was being written at the time. Everything Lange wrote afterwards was charged with urgency and a mysterious threat. There is a suspension of meaning, carried into the realm of action. In People in the Room, this project is fully realized. It is as if she had nothing more to add. It’s tempting to bring up the law of diminishing returns: when a new field opens up in art or science, the initial exploration turns out to be exhaustive, leaving room for only commentaries or variations. After her early works, Lange embarked on a new venture, something no one had ever done before. People in the Room is not a novel to be read for pleasure. Pleasure had been left behind, in the charming scenes of Notes from Childhood.

César Aira

1

When the others reminisced about Avenida Juramento, I was always surprised by how easily they recalled some date destined to endure, some trivial episode, the quiet cheer of whatever had happened that particular day. They rarely strayed from the subject of the house where we spent two years, but when they did, they would abandon it for good, until one day, by chance, someone would mention it again. For me, however, that house was merely the most comfortable and convenient place to keep watch on the other. When someone’s memory faltered and a patient voice corrected the color of a dress, or the night they had called the doctor, my mind would gradually begin to wander, since for me, Avenida Juramento would always be—at least on first hearing its name, though later it could be other things—a dimly lit drawing room looking out onto the street, with shadowy corners, and three pale faces that appeared to be living at ease. That drawing room wasn’t ours, and even though I wandered Avenida Juramento in search of something forgotten, hoping to make that something perfect and perhaps come to prefer it, I managed only to cling to that last half block, which was enough to transform the street into my favorite, understandably my favorite.

Of course, not everything happened at once. Just as for the others, our house soon became a home—with their list of newly heard voices, the slowly acquired habits of long neighborhood and courtyard conversations, unexpected friendships by the mailbox, or when closing the shutters, or arriving from the station in a carriage with the hood drawn down—for me it would become meaningful only later, much later, when they no longer spoke of that house, and I had stopped watching the other. That’s why for a long time I would seem distracted, as if arriving late to the memory of our house, since first I had to set the other one apart, whole and intact in my memory, so it wouldn’t trouble me.

But nothing happened immediately; the various episodes unfolded slowly, and only I was to blame for not meeting them sooner. Perhaps I spent too long in my bedroom; perhaps I could have been more patient and watched the street from the beginning, but I preferred to spend time in my room which, at last, had a view onto a courtyard. A long time passed before I became interested in that other house and its invisible occupants. Whenever I went out for a walk to Avenida Cabildo, I would scarcely glance at the house across the way, silent and well-kept, with little to distinguish it from the others except the look of a vacant house, one only occasionally opened up. But even in this I was mistaken, since I hadn’t been patient enough to wait and see whether anyone was closing the shutters. Nor did I pay much attention to the windows with their light, sheer curtains, which I would later come to find so essential.

The house had two low balconies facing the street, separated by a doorway with dark, stained-glass windows that made it impossible to make out what was going on inside. Only much later did I pay attention to those details, since at first, assuming the house was unoccupied, under the care of a landlord, I liked to glance at it carelessly when, after stepping down from a carriage, I would turn to pay the driver as he held out his hand from his seat. Then, from under the hood of the carriage, sometimes, or over the horse’s back, I would look at it once more, knowing it was there, safe, and I imagined it wouldn’t be long before a window opened and a hand slowly emerged to close a latticework shutter. Or perhaps I would be disappointed if I noticed, suddenly, the same hand tracing a name on the misted glass. I could never bear to see a name written on a train window, an arrow-pierced heart carved deep into a tree trunk. Later everything changed, but in those days, so many things troubled me that the things to which I was most drawn became obsessions, like people who told of long illnesses, like freshly planed wood, black velvet. But for that to happen, I would need to spend hours on end keeping watch over the house across the way.

Nor was the house even mentioned at first, or perhaps someone spoke of some incident without my hearing it; even so, whatever they said wouldn’t have piqued my interest, since much later, when it was all over and anyone mentioned the house, it was like when a portrait of a loved one is revealed, and those who see it fail to grasp its subject’s mystery, the grudges they might bear, their most closely guarded and beguiling traits.

Everyone was wrong about the house. It mattered little if the others were wrong, since it never interested them, not even later, when they found out about my visits. But me, I shouldn’t have been wrong. Whenever I came back from a stroll down Avenida Cabildo, I would cross the street just a few paces before reaching the house, and I was never stirred then, even from afar, by the anxiety that would later seize hold of me as I waited to catch a glimpse of something behind the curtains. I should have sensed and searched for the hand that could trace—without troubling me—a name on the glass; the worn-out silences, the lovely, heavy silences beneath the lamp. But I was in the habit of crossing the street diagonally, since I was drawn more to the bark of a tree by the path in front of our house. Until one afternoon when I decided to come closer to the house across the way, as close as possible to its balconies, its dark doorway, and at the last minute I was distracted. They understood when I told them much later, and they forgave me, and perhaps loved me more for it, as if they thought me a little hopeless, but as we spoke, that didn’t prevent something like a “What a pity,” disconsolate, yet almost without regret, from rendering the best part o

f that evening and many others useless, since behind that “What a pity,” so unwavering and decisive, lay two months of faces behind a window, of white gloves that never grew old, of a dead horse lying in the street, and many other things already past of which we later came to speak, but most of all her voice, her voice so much like mine.

2

My bedroom lit up suddenly and flashes of lightning flooded its corners, leaving them separate and distinct. I kept watch, waiting for the flashes, trying to pass unnoticed so no one would ask me to close the shutters. Unblinking, my eyes wide open, I watched as they made the shadows tremble, split the sky with their flickering lines, lingering, for a few moments, behind my eyes. If they’d seen me from across the way as I collected as many flashes as I could, so they would last a few seconds longer behind my eyes, perhaps they would’ve told me it was useless to resist fate, since soon someone asked me if I wouldn’t mind closing the shutters on the drawing-room window facing the street. I stood up, vexed. I disliked for the house to be closed. To me it always seemed necessary to watch a storm. This time, though, I had no chance to be angry because I forgot about everything, and unknown to anyone, just like that, suddenly, without warning, without turmoil, without dead horses, without any midnight knocks at the door or even a single cry during the siesta, for me the street had begun.

I went slowly towards the darkened drawing room. I remember seeing my reflection when I passed the tall mirror on the dresser, just as the oppressive silence of a flash of lightning deranged the shadows. I don’t know why I was entranced by the sight of my own reflection flung into the mirror by the lightning. When the mirror faded, I opened the window and waited for a white flood of light. But there was only a clap of thunder that made the things in the cabinet tremble. My favorite tree was shaking, and seemed to me like less of a tree. I was about to reach out to close the shutters when I was drawn to a window with a light on in the house across the way. I felt a little ashamed to close our shutters when its light was falling so boldly onto the street. I lowered my hand, closed the window, and stayed there, spying from behind the curtains. And at that moment—as if everything had been prepared for me to attend this meeting with my appointed destiny—I saw them for the first time, began to watch them, and, as I watched them, slowly examining their three faces in a row, one barely more elevated than the others, it seemed to me that I held—like the suit of clubs in a game of cards—the pale clover of their faces fanned out in my hand.

They were sitting in the drawing room, one of them slightly removed from the others. This detail always struck me. Whenever I saw them, two of them sat close together, the third at a slight distance. I could make out only the dark contours of their dresses, the light blurs of their faces and their hands. The one sitting farthest away was smoking, or at least so it seemed to me, since her hand rose and fell monotonously. The other two remained still, as if deep in thought, before turning their faces in the direction of her voice. Then I managed to make out, beside one of them, the small flare of a match being struck. I longed to meet them. There appeared to be drawn-out lulls in their conversation, and they seemed to be enjoying the storm. They didn’t seem to mind that someone might be able to see them from the street. I watched them as if I’d finally found something I’d been seeking for a long time, without knowing what. They seemed to me like the beginning of an accidental life story, without greatness, without photograph albums or display cabinets, but telling meticulously of dresses with stories behind them, of faded letters addressed to other people, of the kind of indelible first portraits that are never forgotten. The lightning wasn’t bright enough to illuminate the pale areas of their faces, or at least I didn’t have time to collect the paleness, since I was more drawn to the lightning. But no sooner did the flashes vanish than I returned to them, and discovered them unmoved, arranged in the same order. I was certain now that from that house, at least, it would be useless to await the hand that would emerge to meet the rain, which would separate the house from that beautiful night that shook the trees and awakened an urge to travel in the dining car of a train. They seemed so passive, so free of futile or impulsive desires, that I felt suddenly touched, and longed to cross the street, knock on their door, and, when they invited me in, to sit in an armchair in that same drawing room, light a cigarette, and wait for one of them to say, “Make yourself at home,” and to feel so truly at home that I wouldn’t even need to tell them my name or to learn theirs, but rather take their faces, as if bidding them goodbye, and, just by looking at them once, never forget them.

Later, when they sat in the dining room, I thought no harm could come to them, as long as they kept sitting there, in the faint light of the lamp, but that safety didn’t extend to the drawing room. It was around the dining table that they seemed safe. I thought, too, that they were hiding something tragic, that it would be beautiful for them to be hiding something, or remembering something dreadful, inevitable, endless; and it seemed that to please me, that something (though I soon thought it absurd) should be some still-unpunished deed, committed in another house, and that only she—the one who sat apart from the others, with the white blur of her hand lifting the cigarette to the white blur of her face—should know; but she wasn’t guilty, she would just know.

Just as I started to feel a thrill, someone called for me. I opened the window and closed the shutters very carefully. After an hour, the storm died down. I announced that I was opening the shutters again to watch the street, which, in part, was true, since I wanted to listen to the steady patter of drops falling from the trees, as if prolonging the rain after it had ceased.

When I opened the shutters, I spied them in the same place, discernible from the pale blurs that scarcely animated the dark room. Then I returned to my bedroom and got into bed, but before falling asleep, I thought the important thing was for them to be there. I also remember thinking—though I thought it fleetingly, because it seemed unfair—that I would like to see her dead.

3

The next morning, as soon as I awoke, I had a feeling something was going to happen, that on some unheeded calendar, someone was marking the day with a cross, and as I recovered them—scanning the three faces that had crossed the street during the storm—I knew at once what made that morning different from any other: the house across the way, my anticipated vigil. As if I’d planned it while I slept, I’d already resolved to watch them, to spend the afternoon sitting in the drawing room by the window facing the street. No one would be surprised to see me there, pretending to read.

The morning passed and no one stirred, other than the maid, who answered the door twice. The sun shone directly onto the windows of the house across the way. The evenings were already drawing in, and I remembered that at teatime we would often turn on the lights. I was also glad the dining room in my house didn’t face the street; that way I would be able to keep watch on them freely.

At half past five, when I returned to my place in the drawing room, I found that the fading light scarcely allowed me to make out their faces in the gloom of their dining room, but I was soon comforted when one of them—I don’t know which—turned on the light, then went back to her place at the table. They stayed there for almost an hour, while I commenced, with difficulty, the story of their faces. It was impossible to tell whether they were eating anything; I could see only the lighter parts—their hands moving towards their mouths. It was even intriguing not to see them eat; it seemed like a sign, the quiet key to their uneventful evenings. I could make out the faces around the table—two turned towards me, one in profile—and I imagined, to my own liking, the white tablecloth, the silver sugar bowl, the toast, gleaming with butter, that none of them touched, but which none of them could bear to ask to be taken away, though it always grew cold and hard. I couldn’t imagine what they were saying, but I didn’t mind much yet, since at that moment, in those first moments when I claimed them like a possession, like an evening routine only I had the power t

o alter, I didn’t want to try too hard; I didn’t want to rush. I would have time later. Before I examined their painstaking, studied loneliness—I was sure each bore her loneliness without disturbing the others—I wanted to know them just as they were, around the table, a group discovered by chance at the edge of night; and to come to know them in other circumstances I surely wouldn’t miss if I dedicated a month or two, or as long as it took, to watching them. I wanted to come to know countless silent, unnamed, unstoried details, so when the time came I’d be lacking only the tone of their voices, the subtlest differences between their faces. I knew, if I was patient, I could have their finished portraits just the way I liked finished portraits to be: for them to be missing something only I knew how to add, a detail forgotten at the last minute, perhaps a muffled sob, impossible dreams, a sudden desire to close all the doors, the strangest fear, a table with its mournful game of solitaire, and that which is almost always lacking and must be added, hurriedly, belovedly: a precise, remorseful memory, or the neatly linked, untangled memories that sometimes appear in a face, which, when it is shown or described, is like a photograph album whose pages can calmly be turned. I wanted almost nothing to be missing when I finally approached them, to lack only one final piece, the last detail to be added to a familiar face.

People in the Room

People in the Room