- Home

- Norah Lange

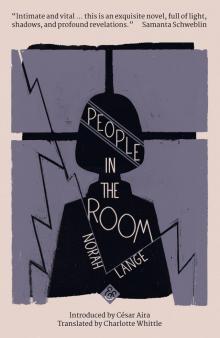

People in the Room Page 13

People in the Room Read online

Page 13

I crossed the street again, looked back over my shoulder once more, picked up my suitcase, and went into my house. It was already time for dinner. Everyone greeted me as if I’d come back different from before, not realizing the change was more recent and distinct. Though I felt sorry for myself, I pretended to be happy, and announced some vague plans to work on my Latin and spend more time reading. For the first time, I drank more wine than usual, but I couldn’t eat, since I needed to keep talking. And as I spoke I asked questions through which my fear traveled, unheard. Wasn’t there any news in the neighborhood? Had the trees been pruned, and my favorite one, too? Were there any new neighbors? Then, suddenly, I asked, “Has anyone died on our street?” and everyone looked at me as if death were some distant, improbable thing, something mentioned only then for the first time in our house.

“No. No one has died … ” they answered.

How could it be that no one had died behind the shutters, gathering letters upon blue dresses over my impeccable hands, though they’d never spoken of my hands and were happy to have met me? And I kept asking, “Are there any letters for me?” And someone answered that there weren’t, in a sad tone because the difference was drawing nearer, promising nothing, and then I went into my bedroom to change my clothes, and came back to my family to talk of other things and relieve them of my anguish, while I slowly prepared myself for a final gaze, since the next day I would cry at them in hatred, I would cry at them that they should be ashamed, that they should die of shame, and that night would be the farewell, the only way of gathering together all that was tender and could be forgiven.

I went back to the dining room, drank some more coffee, and lit a cigarette, watching everyone with the same demeanor as before, until each of them went to their room and I was left alone with the terrible emptiness, with the thing I never shared. I still didn’t want to look out into the street, since perhaps later, within an hour, I would find the faces, as in their usual portrait, pale and insistent, slightly out of breath since they’d had to come running to arrive in time for their nightly habit of being watched.

Much later—knowing their routine—I decided to look. In silence, as on the first night, I pretended not to be expecting anything from the street—the only thing missing was my silhouette cast into the mirror by a flash of lightning—and I went towards the drawing-room window. I tried to forget everything, so I could see, as if suddenly opening my eyes and gazing at them for the first time.

When I finally looked, the drawing room was still in darkness behind the closed shutters. I was quite surprised to feel the blood drain from my face. I felt as if something was gently ushering me into mourning, and I went back to my bedroom. I lay down in bed, and, as if carrying out the last wishes of a loved one who had died, slowly, meticulously, I directed the three of them towards medicine jars as they took mistaken doses and their reclining faces shared among them a packet of letters and a portion of my sadness, which didn’t cease to stir until I fell asleep, leaving room for their possible, true deaths.

24

Perhaps I didn’t deserve them, but I watched them. God knows I watched them selflessly, longing for them all night, unreconciled between dreams when I turned to stare at the wall before falling asleep again, leaning into my unwitnessed void, so much like the wall, inventing conversations with people I knew who were incapable of discerning the three faces—impossible to glimpse anywhere but the drawing room—without assuming, immediately, that I was telling them about a portrait; a beautiful portrait that perhaps could be forgotten. Of course, of course I was disconsolate, and found comfort in the white wall—with its light patches of rough whitewash—and all because of a portrait. It could only be a story about a portrait, a feat for my age, a voyage through three faces, though I couldn’t even specify the color of their eyes, the way they did their hair, the tentative shape of a smile, as my anger grew and I slipped in and out of sleep, the wall lost to me once again.

What did a story of a portrait matter, when the others recited emotionless weekends, jobs, newborn babies, all of which could become entwined—but without choking it—with something as selfless and discreet as a portrait that scarcely changed after two months of being watched! Nor could they—those possessed of all that was ordinary and natural—learn to control their skin when a shiver ran over it; but they paid it no attention, though it was only a portrait that was beginning to intrigue them, because it mingled with their first high heels, with the rush to get home, with the latest film, and they couldn’t see that the shiver might herald the beginning of a story, something I could keep telling—like the three faces at the edge of a storm—and perhaps I could add something to those faces, so the others would keep listening until they were persuaded it wasn’t a portrait, and said, “Tell us! Why don’t you tell us?” But I noticed their anticipation of a rendezvous, a new hat, or heard them grumble, and kept to myself that which wasn’t a portrait, since not even as a portrait was it possible to tell with such urgency, without those long pauses that perhaps helped emphasize their demureness and make it more ordinary and easier to grasp.

Perhaps I didn’t understand them, but I watched them, God knows I watched them until piece by piece they invaded me, scratching at me, walking through me. It wasn’t possible to have watched them so completely only for them to leave me from one day to the next, with my gaze fallen and nothing to collect, as if I should be content with what remained of them inside me; forcing me to use up what I had inside and what I might’ve been able to keep in reserve; forcing me to be brave when I didn’t want to be brave, or strong—it seemed stupid to be strong—urging me to traverse a whole night with my gaze destroyed, shattered, with no desire to begin anything anew, if indeed I ever again watched anything that I had to take back to my room, so as to contemplate it before I fell asleep.

What mattered wasn’t what I might watch next, after having loved and hated them enough. What mattered was that I had stayed in my place, selfless and longing for them, and that they hadn’t prepared me for my gaze to return, to gradually retreat towards what I used to watch, until I felt the desire to cry, “What a pity they aren’t dead!” since it would’ve been a different and inexorable pain to complete my gaze with their lifeless faces in a white row, smokeless and reclining, finally laid out in their deaths, with no time for any preparations, and to discover a mouth slightly larger, an eyebrow with a clearly defined and sudden arch above a coin someone had placed over an eyelid, saying to myself over and over, almost numb from so much suffering, “If only they could at least have died on time!” convinced they hadn’t died, that their deaths were impossible across the way from my house, when no one even knew who they were.

But no one had noticed anything—I was sure—and they weren’t pretending either. It was simple. No one had noticed anything while I was watching them. It was almost a miracle! No one had noticed a thing. That meant they hadn’t noticed my way of keeping watch on the house across the way, or that someone, in my absence, must have closed the shutters for the first time, to prevent its bold light from falling onto the street, since they were willing to die.

“You haven’t noticed a thing!” I would have liked to cry. “In two whole months, didn’t you notice anything, not even while I was away, couldn’t you even see if something was missing from their faces? I won’t say my gaze. That would be too much to hope for. But something! Won’t you tell me what it is you think about, what you spend all day looking at?” But perhaps it was better that way; I alone, verifying the essential, I alone with my gaze, which would have to get used to being more careful.

When I awoke with the whole day ahead of me, I tried to spurn the house in darkness; I decided not to get up until the afternoon, to wait until the streetlamps were lit before my final journey to their inconstant faces.

“She’s tired! She won’t get up … ” those who’d noticed nothing seemed to whisper, closing doors, while I felt those hours of weakness as a way of grieving. Everyo

ne came to my room. Someone prepared me a glass of port with egg yolk, and I thought to myself, “I’m suffering from a locked-up house,” as I pressed their faces against my pillow.

And all the while, over the lunch tray and the glass of wine, I braced myself. Everyone seemed to be carefully preparing me as if that day was the beginning of my strictly observed mourning, the solemnity before the news arrived. And I kept dozing over my slices of toast, and from them a carriage set off, the carriage that would stop a few feet before a house of convalescents edged with soup and a voice that said, “Be quiet.” Yes! Be quiet, because anything is possible once the horse has stopped: slit wrists, a nightgown damp not from the heavy drops of their own tears, but from the slow trickle of their blood; a delicate, belated hemophilia preventing them from turning over, soaking their hips, their bodies stuffed with sawdust beneath their glued-on heads; their pink porcelain necks above their collars. Perhaps all that remained were three reclining busts without the backs of their armchairs, beside their precise veins with a little cut, or each bleeding to death in her own room, so neither their happiness nor their fear nor my absence—I, the faithful witness—would show over the top of the letters; my absence, yes, my absence, because even if it wasn’t true it was beautiful to suppose my gaze was the one they’d chosen for their modest end, without any cries or sealed envelopes, behind the locked house no one would open until I arrived to attend to their deaths and receive condolences for all that had happened, which I must gather together so it would all die at once.

But I had to think of getting up, of challenging them, of crying that I’d never return because I deserved more than a dark house and a lack of letters, even though, had they written to me, I wouldn’t have recognized the restrained calligraphy whose neat, pointed letters corrected schoolwork and expressed the most terrible things, when I didn’t even know their names. And I asked again, “Isn’t there any news in the neighborhood?” and it was a relief to know that they weren’t lying; that the only thing to have happened was my fear.

Someone advised me to stay in bed all day, as if dressing me in black, but I thought I should throw the white gloves, with their enduring talcum powder, in their faces—not noting the danger, if it existed—as they came and went and watered the ferns imploring me to sleep, and I opened the trunk where they kept their riding boots and found only a portrait stuck in a glass frame and the ribs of a fan whose lace was lost forever, convinced their memories were mere remainders, that they had only their faces, flawless and intact, and the two portraits that reached my waist, which one day would make me laugh because they reached my waist, and perhaps one day I would tell them, when I was convinced of my hatred, laughing at the height of my waist.

I was almost happy not to visit them that evening, to put on airs after my absence, with the weariness and headache of those who’ve been away on a journey, as if it were essential to affect a headache I didn’t have, in the hope that perhaps I’d decide to wait another two days—to teach them a lesson for their silence, their selfishness, their constant talk of death when they didn’t dare take their own lives—while I stored away their faces, leaving them for another day, and discovered it was easy to leave them one more day; so easy it made me smile, and say to myself, “I’ll leave them for another day,” then turn towards the wall, or read, halfheartedly, another page.

But it was all useless, since I loved them too much. As soon as darkness fell on the courtyard, and someone closed a window, I began to feel impatient. By now they would be having tea, a sad, silent tea that filled me with pity, forcing me to admit that they weren’t prepared. Perhaps she would murmur, “She’ll come this evening,” and there was a slight chance, the slightest chance—just barely—that I was the person they might like to see, since I was the one who knew they weren’t prepared. But I wouldn’t visit them. I would wrap myself up warm and sit by my window, recovering from not seeing them, not crossing the street even if they were in the drawing room. Not only did it seem impossible to cross the street, but it suited me to be sad; I too deserved to be sad from time to time, because I’d never stopped watching them, while they, on the other hand, repaid me with their dark house. I didn’t want to complain, though, but simply describe to them my return, the accuracy with which I selected every detail I loved and which was essential for returning to their faces. The simplest thing, as always, turned out to be the most terrible. It would be enough to tell them over and over, “Your faces were gone … Your faces were gone … ” for their faces to howl with shame, with regret, with lack of tact, and I kept rehearsing how I would tell them about my afternoon, as I pulled on my stockings, rehearsing my true anguish because I had plenty of time, and because their faces moved deep within me, confined, as if struggling, as if bumping sadly against one another for lack of space, since fear took up nearly all of the space and buried itself in their eyes, and disheveled them, driving them mad with shame; but fear had won and now I was standing, without having dressed, wrapped in a long coat, ready to sit in the drawing room.

I remember praying for there to be room for their faces, for them to be there, and not force me to mourn them so soon, to mourn their untimely deaths, to be the person who removed the flowers before tearing open an envelope. Yes, I prayed, and perhaps it was the last time I ever prayed anything clear, definitive, because then other episodes mingled together, and I had to pray differently. I remember, too, everything I did before reaching the drawing room, sure no one was there, and then I looked at myself in the mirror, but there was no flash of lightning. It was better that way; I needed to stay calm, and even my favorite tree would have been a distraction. Without looking towards the house across the way, I pulled up a chair—the most comfortable—to the window, in the certainty that I would stay there, crying gratefully as soon as I saw their faces, convinced they would be there and needn’t be ashamed, as their fear began to fade and they could go back to smoking in peace.

Once I’d prepared everything: the armchair, an ashtray, the shutters wide open, not looking towards the house across the way because I wanted to sit comfortably—I would feel braver if I was sitting comfortably—I sat down, covered my legs, lit a cigarette, and only then did I lift my head to collect them, without making any mistakes.

Perhaps at the last minute something cried at me not to do it because I didn’t deserve their faces full of shame behind the closed shutters, because I looked and was ashamed to be wrong, not to have prayed enough; because I looked, convinced I had never come back and the glass of port was to blame, and I smiled to myself as if at a wake for the dead, out of sheer fear, out of the sheer inability to undo anything as they watched me, and I didn’t want to be brave; because I looked and began to drive them mad with the north wind, “Where were you last night?” beside the unworn white gloves and the cautious man, because they were three criminals with portraits that reached my waist; because I watched and burned my hand on the useless cigarette of my first gaze returning to their faces that abandoned me beside all that I didn’t know and my demure language trying to sound the part, while I glimpsed their beds standing on the path and blushed at the nude litheness of the way they turned as they slept; with the portraits staring at the wall above the dresser that seemed unimportant in a tall green carriage paneled with wood towards another house; fleeing from all they had listed, not keeping watch on the carriage or the final conversations I didn’t hear, emerging surreptitiously in a wilted clover towards who knows where, after they carried the trunk over their dead father unaware of the belated slit wrists and the discreet wine though a spider passed by, because they were happy to have met me; and the horses set out without me and I couldn’t go on as my anguish clung to it all and the three faces sketched brief signs like telegrams, spilling over the edges of a white notice with paid reply, until signs announcing “House for hate” began to drive me mad, because “House for rent” and beside it a set of keys were no more than a ribbon of wood upon their faces misusing my absence as they waited for the horses I

liked to set off to follow them in a carriage where an unrequited love was missing from my gaze that couldn’t go on, that didn’t know what to do, or where to look so as not to grow used to the first walls of anguish, because “House for rent” would forever be the three faces I loved, and I cried, trying to help them, trying to prevent my gaze from knowing them by heart.

Dear readers,

As well as relying on bookshop sales, And Other Stories relies on subscriptions from people like you for many of our books, whose stories other publishers often consider too risky to take on.

Our subscribers don’t just make the books physically happen. They also help us approach booksellers, because we can demonstrate that our books already have readers and fans. And they give us the security to publish in line with our values, which are collaborative, imaginative and ‘shamelessly literary’.

All of our subscribers:

receive a first-edition copy of each of the books they subscribe to

People in the Room

People in the Room